By Cristiane Albuquerque

At a moment when the credibility of scientific knowledge is under attack, Dr. Elisa Reis, professor of sociology at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), is firm: “The more we drive home the idea that scientific knowledge is superior, the more we are helping propagate this type of [anti-scientific] thinking. Scientific knowledge isn’t superior, but it has standards and is subject to certain protocols. That’s why we must uphold its specificity; otherwise, people will say the earth is flat just as assuredly as we affirm it isn’t.”

Social scientists must be propositional when criticizing current models. If we only criticize them, we contribute to the well-known polarization of opinions

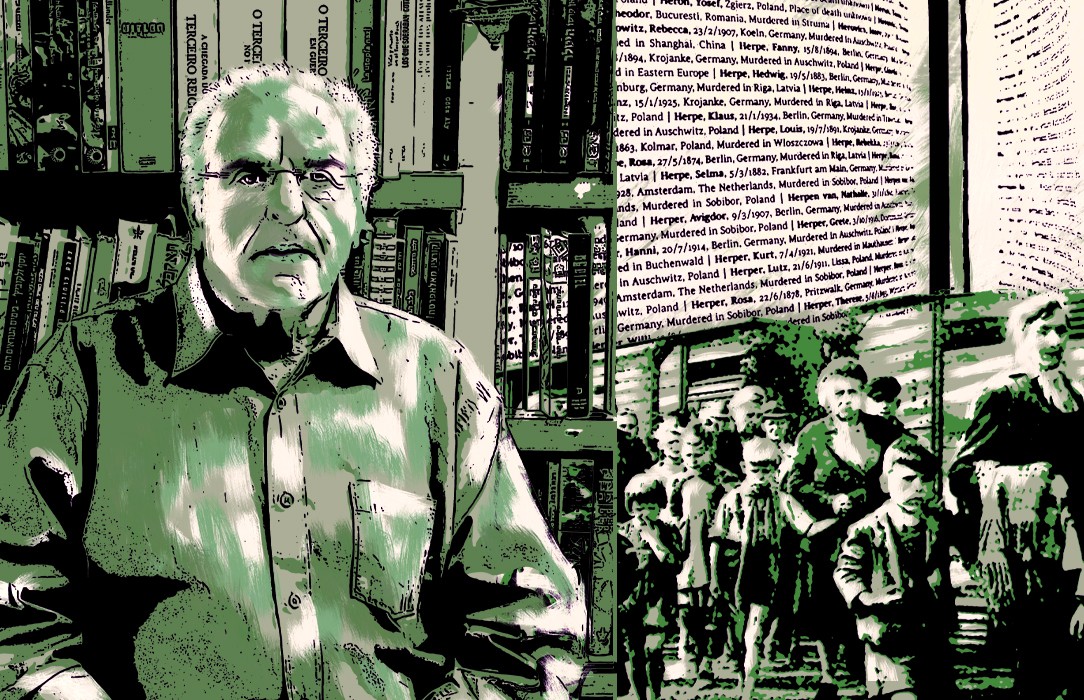

This statement was made during the talk “Why Social Sciences?” held as part of the regular History Lecture Series sponsored by the Casa de Oswaldo Cruz’s Graduate Program in the History of Science and Health. Dr. Reis, who holds a doctorate from MIT and is a member of the Brazilian Academy of Science (ABC), defended the public’s right to reliable scientific information.

“Science is a human right. Depriving the public of access to scientific information is extremely serious. Everyone should share in scientific advancement and its benefits, know what science is good for, and know how much public policy relies on this knowledge,” she said, pointing out that the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, signed in 1948, advocates that everyone has a right to science. The lecture, held on September 19, 2019, was moderated by Marcos Chor Maio, a researcher and professor at Casa de Oswaldo Cruz.

Dr. Reis also warned about the need for strategies to revalorize science. “We have the expertise to interpret and explain the world’s current crises, search for alternatives, and, above all, foster dialogue concerning a variety of issues. We cannot allow limited visions of the social sciences to be normalized,” she argued.

Dr. Reis listed the challenges that the social sciences face in containing the advance of neo-protectionism, neo-nationalism, and neo-populism at this time of global transformations. “Neo-protectionism is a threat to the world market, in that the system bans or inhibits the importing of certain products through the taxation of foreign products. The case with neo-nationalism is that it endangers solidarity and social cohesion as a whole, while neo-populism is a threat to democracy. Accordingly, the social sciences must engage with each other in a constructive fashion and position themselves against these ideas, which present a global risk and challenge democratic forms of governance,” she said.

During the event, Dr. Reis also underscored the role that transdisciplinarity plays in the social sciences and the interpretation of the world’s current crises. “We must understand knowledge as plural, while recognizing each field’s unique characteristics and contributions, so we can pursue alternatives. Social scientists must be propositional when criticizing current models. If we only criticize them, we contribute to the well-known polarization of opinions,” she advised.

“No scientific endeavor can be justified unless there is an understanding of social responsibility”

In Dr. Reis’s opinion, the idea of progress should be a normative ideal, and social science should, in a responsible manner, ascertain what is needed to promote life in society. “All science is social; no scientific endeavor can be justified unless there is an understanding of social responsibility, grounded in such values as the pursuit of well-being, equality, dignity, security, and sustainable growth. This is why it is imperative for us to rethink the notion of progress, because without this notion, there is no point in thinking about scientific activity,” she emphasized.

From this perspective, progress, or social development, should stay in tune with mechanisms circumscribed by reality. “Our perception of progress is not incontrovertible. There is nothing natural that leads to progress or social growth. If we don’t ask ourselves how it is possible to improve things or how to do this, things will not change,” she said.

Social sciences contemplate new agendas for the twenty-first century

Dr. Reis also talked about how the social sciences made a historical contribution to the construction of the nation-state. According to the researcher, social sciences and sociology have redefined their concerns over time. “In the context of the modern world, the big themes in the social sciences were the Industrial and French Revolutions, along with the idea of progress. In the 20th century, the social sciences debated the decolonization process, the building of nation-states, the green revolution, as well as the issues of poverty, inequality, and social exclusion, which actually remain in discussion today, but with other overtones,” she said.

According to Dr. Reis, the major items on the social sciences agenda for the 21st century are globalization, environmental problems, finance capitalism, and changes in the working world, alongside technological singularity, a topic that, Dr. Reis says, has garnered greater attention in light of the perceived risk that machines may come to rule the world. “Singularity is a concept used in mathematics to refer to something unexpected or inexplicable. The question that has been raised is whether, because of artificial intelligence, we might not end up facing the big issue of how to tame machines, how to make machines work for us,” she said in conclusion.

Translated by Diane Grosklaus Whitty