Fiocruz's exhibition shows the crucial role of science, the SUS and affected families in the responses to the disease, in addition to the present challenges

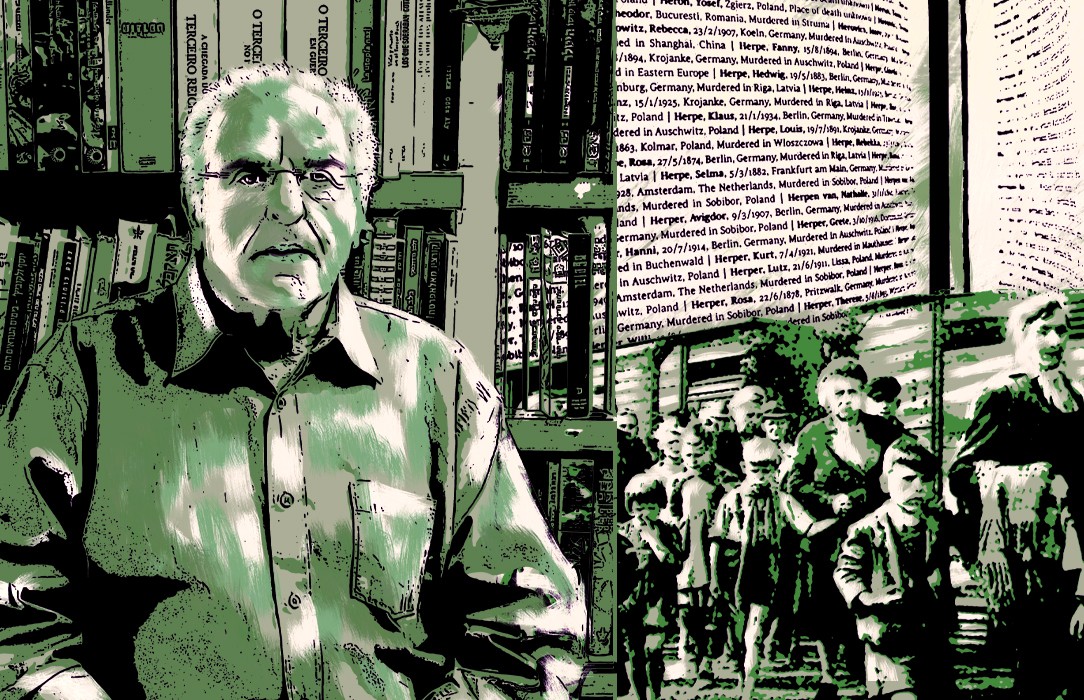

| Image: Maju Monteiro/Zika: the lives affected. |

By Karine Rodrigues

Experiencing the effects of a global health crisis is nothing new for Alice, Juan Pedro, Pérola, Dimitri, Maria Isabel and about 3,000 other Brazilian children and their families. Born beginning in 2015, they have Congenital Zika Syndrome, which has spread throughout Brazil and other countries and led the World Health Organization (WHO) to decree a Public Health Emergency of International Importance on February 1, 2016.

Zika is no longer considered an emergency, but it hasn't disappeared from the national scene. It is an illusion to say that the situation is under control; the problems resulting from the epidemic continue

Brazil stood out when confronting the health emergency, ever since the first cases appeared in the country. It was, in fact, a warning from the Brazilian government about the possible connection between the Zika virus and the increase in births of babies with microcephaly and other congenital malformations that caused the WHO to declare a global state of emergency.

Despite being recent news, the Zika virus — transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, or via blood, sexual intercourse and during pregnancy — has fallen out of focus. And this took place even before the arrival of Sars-CoV-2, which, given its seriousness, has required the full attention of the public healthcare system and private networks.

"Zika is no longer considered an emergency, but it hasn't disappeared from the national scene. It is an illusion to say that the situation is under control; the problems resulting from the epidemic continue,” stresses Lenir Nascimento da Silva, a pediatrician with a doctorate in public policy in the Department of Healthcare Administration and Planning at the Fiocruz National School of Public Health (Daps/Ensp). The researcher is one of the curators of the virtual exhibition called Zika: the lives affected, created by the Zika Social Sciences Network and by the Casa de Oswaldo Cruz (COCOC/Fiocruz), through the Museum of Life.

WHO declared the end of the international emergency in November 2016. Nevertheless, epidemiological data from the Brazilian Ministry of Health includes confirmed cases of Congenital Zika Syndrome in 2018, 2019 and 2020. From 2015 to October 2020, there were 3,562 confirmed cases.

“In 2019, approximately 24% of Zika cases were in pregnant women. We've solved a lot of things, but there is still a lot of uncertainty about Zika. Including about the possibility of a new outbreak. What happens if a new strain begins circulating in Brazil?,” asks the pediatrician.

Zika Social Sciences Network brings together research on the topic

Silva raises the alert based on official figures and also on the work she carries out as a member of the Zika Social Sciences Network. Established in 2016 by a group that included current Fiocruz president Nísia Trindade Lima and ENSP researcher Gustavo Matta as soon as the first cases began to appear in Brazil, the initiative brings together projects on the subject, including a scientific survey on the history of Zika in Brazil. The study highlights the crucial roles of Brazilian scientists, families and the Unified Health System (SUS) in the response to the disease..

It is a narrative from the perspective of families, women, and children, but also from that of researchers in the social sciences, biomedical researchers, healthcare professionals, universities, and research institutes in Brazil and abroad, in addition to the SUS and its networkcom

Findings from the research carried out by the Zika Social Sciences Network are part of the virtual exhibition Zika: the lives affected, officially inaugurated in March 2021. Developed through a participatory curation process, coordinated by Silva, Mariana Albuquerque, also from ENSP, and Fabíola Mayrink, from the Museum of Life, the exhibition tells the story of the epidemic through its different social and institutional actors. “It is a narrative from the perspective of families, women, and children, but also from that of researchers in the social sciences, biomedical researchers, healthcare professionals, universities, and research institutes in Brazil and abroad, in addition to the SUS and its network,” describes Silva.

The working group started the study in 2016, with evaluations and fieldwork. Later, it joined the Casa de Oswaldo Cruz, via the Museum of Life, so that the study could be disseminated in the form of an exhibition. Designed to be on-site and itinerant, the show was to be inaugurated on Fiocruz's 120th anniversary, at the end of March 2020, just when the new coronavirus pandemic closed cities in an attempt to contain the unconstrained expansion of the infection in the country. The work was then reinitiated to transform it into a virtual exhibition.

Museum of Life embraced the challenge of transforming the research into an exhibition

A biologist by training and head of the Museum of Life's Itinerancy Service, Mayrink had already developed other initiatives for scientific dissemination, but the exhibition on Zika involved new difficulties.

If it hadn't been for this network, this public policy called SUS, with the relationships established within it, we would not have had such quick answers

“Exhibitions as a product of research are always a challenge, no matter how many I've done. There were other challenges, beginning with the health emergency that began on the eve of its inauguration. Converting an exhibition developed for a physical space, which had not yet been finalized, without having evaluated the interaction with the public, was a new experience, especially developing it online,” she observes.

Addressing a delicate issue through work that strives to approach different audiences required sensitivity, says Meyrink, highlighting the participation of families affected by Congenital Zika Syndrome when preparing the exhibition, who played an important role in the responses to the epidemic.

"It was especially the women — who met in healthcare service waiting rooms and had the courage to join together and participate in the production of knowledge — that contributed a lot to the research in relation to the congenital syndrome, on the issue of intersectoral policies and social protection policies. They are still very active today, and not only in relation to Zika,” says Silva, adding that they have joined together with other associations to discuss issues related to disability in particular.

The challenges are even greater with Covid-19. With the suspension of the multidisciplinary care that these children need — speech therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, etc. — and of classes, their development is compromised. This lack of assistance adds to the economic difficulties: expenses are high and the caregiver, usually the mother, ends up leaving the labor market to stay with the child. Not everyone living with Congenital Zika Syndrome has been granted a lifetime pension, worth the monthly minimum wage.

“If you listen to the stories they recount about the need for access, medication and, now that the children are older, schooling… Their discourse is clearly that of those who live, and act, in a very conscientious way. If it hadn't been for this network, this public policy called SUS, with the relationships established within it, we would not have had such quick answers,” points out the researcher from ENSP.

The photograph that illustrates this article, by Maju Monteiro, is part of the exhibition 'Zika: the lives affected'

Translated by Naomi Sutcliffe de Moraes